An Analysis of DRG Profitability and Cross-Subsidization in Academic Medical Centers

Abstract

Background

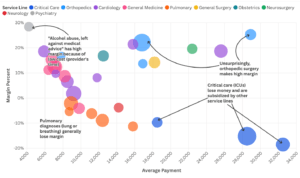

Academic medical centers operate as financial paradoxes: the most essential community services systematically lose money while profitable elective procedures generate margins that subsidize unprofitable emergency care. This analysis examines profit margin patterns across 30 high-volume diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) to quantify cross-subsidization relationships within a representative academic medical center.

Objectives

To quantify profit margin variation across high-volume diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) in a representative large academic medical center, identify specific cross-subsidization relationships between profitable elective procedures and unprofitable essential/emergency services, and provide hospital leaders and policymakers with concrete data on the financial architecture that enables comprehensive care delivery.

Methods

DRG profitability patterns were analyzed using Medicare cost report data, calculating margins as the difference between Medicare payments and estimated costs for each diagnosis category. Service lines were categorized by clinical specialty and analyzed for volume-margin relationships.

Results

Orthopedic procedures generated positive margins averaging 22%, while critical care services demonstrated negative margins of 15% per case. Emergency conditions consistently showed negative margins requiring subsidization from elective procedures. Analysis reveals that profitable spinal fusion procedures generate sufficient margin to offset losses from approximately three sepsis cases.

Conclusions

Academic medical centers operate through cross-subsidization models where profitable elective procedures fund unprofitable emergency care. Understanding these dynamics proves essential as healthcare transitions toward value-based payment models and faces consolidation pressures that threaten comprehensive care delivery.

Keywords: hospital economics, diagnosis-related groups, cross-subsidization, academic medical centers, healthcare strategy, DRG profitability, emergency care, elective procedures, value-based payment, Medicare margins

Introduction

Hospital closures of emergency departments, psychiatric units, and trauma services while maintaining profitable surgical programs reveal fundamental economic tensions within American healthcare delivery (Kaufman et al., 2023). These patterns demonstrate how profitable services such as orthopedic surgery or cardiology subsidize unprofitable emergency medicine, a phenomenon particularly pronounced at academic medical centers that serve as community safety nets.

Current healthcare economics face unprecedented pressure from multiple directions (MedPAC, 2024). Value-based payment contracts expand across the industry (McWilliams et al., 2023). Medicare margins continue compressing. Hospital consolidation accelerates, often resulting in service line eliminations that prioritize financial performance over community needs. Academic medical centers must navigate these pressures while fulfilling complex missions encompassing emergency care, medical education, research, and community benefit obligations. These pressures directly threaten the cross-subsidization model that enables comprehensive care delivery. Without understanding these subsidization requirements, hospital executives risk inadvertently destroying their capacity to provide essential community services.

The Cross-Subsidization Challenge

Despite its critical importance to healthcare strategy, cross-subsidization remains inadequately quantified and poorly understood. Hospital executives make strategic decisions about service lines, capital investments, and resource allocation without comprehensive data on how profitable services support unprofitable but essential community care. Policymakers debate payment reform and hospital consolidation without fully grasping how these changes might disrupt financial relationships that enable comprehensive care delivery.

Research Objective

This analysis quantifies cross-subsidization dynamics by examining profit margins across 30 high-volume diagnosis categories at a representative academic medical center. The findings provide hospital leaders with concrete data on subsidization requirements while informing policy discussions about payment adequacy and healthcare market structure.

Background and Context

Healthcare markets violate fundamental principles of traditional commerce. Emergency medical conditions create price-inelastic demand where patients cannot comparison shop or defer treatment. Federal regulations then require hospitals to provide emergency care regardless of payment ability. Finally, insurance companies and Medicare set reimbursement rates independent of actual treatment costs. All of these factors combine to create systematic market failures where normal supply-demand relationships break down.

Academic medical centers face additional complexity due to multiple mission requirements beyond patient care. Teaching responsibilities add costs not fully reimbursed through Medicare graduate medical education funding, while clinical research activities require infrastructure support beyond typical community hospital operations. Community benefit obligations under tax-exempt status demand provision of services that may not generate positive margins. Complex case referrals from other institutions typically involve sicker patients with higher costs – but identical DRG payments. The confluence of these factors creates disparate payment realities for academic medical centers.

The DRG Payment System

Medicare’s diagnosis-related group system, implemented in 1983, pays hospitals predetermined amounts based on patient diagnosis regardless of actual treatment costs or length of stay. While this prospective payment system controls costs and incentivizes efficiency, it creates financial stress for institutions treating complex cases that exceed average cost assumptions built into DRG payments.

Healthcare economists have long assumed cross-subsidization exists, though empirical evidence remained limited until recently. Lindrooth et al. (2018) provided rigorous proof when they documented that general hospitals systematically reduced psychiatric and trauma services as specialty cardiac hospitals captured profitable procedures – a one-to-four ratio of lost community services to lost cardiac cases.

More troubling, Palmer et al.’s (2014) systematic review of DRG payment systems internationally found consistently negative effects on service comprehensiveness, though the authors downplayed these findings in favor of efficiency gains. No prior research has quantified the specific financial architecture that enables academic medical centers to maintain comprehensive care despite these documented pressures.

Methodology

Cost report data reflects fiscal year 2023-2024 patterns derived from HCRIS submissions and Medicare payment schedules effective for the 2024 payment year. Costs were estimated using institution-wide cost-to-charge ratios applied to total charges for each DRG category. While less precise than detailed cost accounting, this methodology provides reliable relative comparisons and follows standard health economics practices. Profit margins were calculated as: (Medicare payment – estimated cost) ÷ Medicare payment.

Service Line Scope

Analysis focused on adult acute care services with sufficient volume for statistical reliability (minimum 85 annual cases). Several service lines were excluded for methodological reasons: oncology services involve complex payment structures including separate chemotherapy billing that make DRG analysis incomplete; pediatric services operate under different regulatory requirements with specialized funding; behavioral health increasingly uses alternative payment models; rehabilitation services follow separate Medicare payment rules rather than the acute care DRG system.

Analytical Framework

The investigation employed three-dimensional analysis considering volume (total discharges per DRG), margin percentage (profitability per case), and total financial impact (volume × margin per case) to understand both individual DRG performance and system-wide cross-subsidization requirements.

Results

Analysis reveals significant profitability variation across service lines, with clear patterns of cross-subsidization between profitable elective procedures and unprofitable emergency services.

Profitable Elective Service Lines

Three patterns emerge consistently across profitable service lines: elective timing enables optimization, healthier patient populations reduce complications, and standardized protocols minimize resource variation. These characteristics allow certain procedures to generate margins of 15-25% that fund unprofitable but essential services.

- Orthopedic procedures consistently demonstrate positive margins across multiple DRG categories, with major joint replacement procedures showing 22% margins and 380 annual discharges generating substantial aggregate profits. Spinal fusion procedures achieve 25% margins despite lower volume across 150 cases.

- Cardiac procedures demonstrate equally strong financial performance. Major cardiovascular procedures achieve 18.7% margins across 220 annual cases, while percutaneous interventions with drug-eluting stents reach 21.4% margins over 140 procedures. The distinction between elective and emergency cardiac care proves critical here, revealing how timing rather than specialty determines financial outcomes.

- Select specialty services (obstetric and substance abuse services) achieve notable margins through resource efficiency rather than high payments. Substance abuse cases reach 28.4% margins through brief lengths of stay and minimal resource intensity, though volume remains limited at 110 annual cases. Cesarean deliveries maintain 16.8% margins across 155 annual procedures, benefiting from predictable resource needs and standardized care protocols.

Essential but Unprofitable Emergency Service Lines

Emergency and critical care services consistently generate negative margins despite representing essential community functions. High-volume emergency conditions systematically lose 8-18% per case, contradicting assumptions that volume creates economies of scale and revealing fundamental misalignment between DRG payments and actual emergency care costs.

- Sepsis cases – the highest volume category at 420 annual admissions – lose 15.2% per admission while representing the highest volume category at 420 annual cases. Respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation demonstrates 18.5% losses per case across 235 annual admissions. Emergency presentation prevents optimization, intensive resource requirements, and patient complexity extends length of stay far beyond Medicare’s modeling.

- Respiratory conditions systematically lose money across multiple DRG categories, challenging conventional wisdom about pulmonary medicine profitability. Pulmonary edema and respiratory failure cases show 8.9% losses over 210 annual discharges. Pneumonia with major complications demonstrates 6.2% losses across 145 cases, despite pneumonia being considered a “routine” medical condition.

- General medical services reveal an unexpected pattern where complexity and urgency predict financial losses rather than higher reimbursement. Routine conditions like urinary tract infections generate modest 12.4% margins, while complex emergency presentations such as heart failure barely achieve positive margins at 1.8%. This inverse relationship between patient acuity and financial performance exposes a fundamental flaw in DRG payment methodology that assumes sicker patients justify higher payments when the opposite often occurs in practice.

Financial Architecture of Cross-Subsidization

Financial relationships reveal specific subsidization ratios between profitable and unprofitable services that contradict traditional healthcare economic models. Select examples illustrate the effects of cross-subsidization:

- Each profitable spinal fusion case generating approximately $7,300 in margin can offset losses from three sepsis cases losing roughly $4,300 each.

- Major joint replacements contribute $1.4 million annually in aggregate profits despite lower individual margins, demonstrating how volume can compensate for reduced per-case profitability.

Analysis reveals an inverse relationship between volume and profitability that challenges basic economic assumptions about healthcare delivery. High-volume services typically show negative margins while high-margin services demonstrate lower volumes, creating strategic tension that requires sophisticated financial management rather than simple profit maximization. This pattern emerged consistently across all major service categories, defying attempts to achieve both volume growth and margin improvement simultaneously.

Discussion and Strategic Implications

Strategic Considerations for Healthcare Leadership

Hospital executives should immediately assess their institution’s cross- subsidization requirements by conducting similar DRG-level margin analysis. Service line decisions should explicitly account for subsidization capacity when evaluating expansion or contraction. Strategic planning must shift from individual service line ROI to portfolio-level financial sustainability.

These findings fundamentally alter traditional service line evaluation approaches. Standard business analysis suggests eliminating unprofitable operations while expanding profitable ones. Healthcare institutions cannot follow this logic because essential community services cannot be eliminated and because profitable services depend on maintaining comprehensive institutional missions.

Hospital leadership must adopt investment portfolio thinking rather than traditional service line analysis, balancing profitable and unprofitable services to achieve overall mission fulfillment and financial sustainability. This approach requires protecting profitable service lines as essential revenue generators while investing strategically in high-margin services and quantifying community benefit through negative margins on essential services. Standard return-on-investment analysis fails in healthcare settings where mission-critical operations systematically lose money yet cannot be eliminated.

Cross-subsidization dynamics explain resource allocation patterns that appear economically irrational to outside observers but reflect financial necessity. High-margin specialists receive accommodation and resources not because of clinical superiority but because of revenue generation requirements (Casalino et al., 2008). Orthopedic surgeons and interventional cardiologists function as revenue engines enabling entire institutional operations, informing compensation negotiations that prioritize financial contribution over pure clinical metrics. Facility planning decisions that favor surgical services over emergency department expansion follow similar logic, though this rarely gets acknowledged in public discussions about hospital priorities.

Policy and Payment System Implications

Systematic negative margins in critical care suggest potential inadequacy of Medicare DRG payments for complex emergency cases at academic medical centers, contradicting CMS claims about payment adequacy (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2023). Current payment formulas fail to account fully for teaching costs, research overhead, and higher patient acuity typical of these institutions. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission’s recent analysis downplayed these concerns while acknowledging “some variation in hospital costs” without addressing the fundamental structural problems documented here.

Healthcare market consolidation often eliminates essential community services because acquirers rationally eliminate loss-making services while retaining profitable procedures. This approach maximizes financial returns while destroying cross-subsidization models that enable comprehensive care, yet regulatory oversight focuses primarily on market concentration rather than community impact. Recent Federal Trade Commission hospital merger reviews have ignored cross-subsidization effects despite their obvious relevance to antitrust analysis of healthcare markets.

Value-based contracts that reduce payments for profitable procedures without addressing unprofitable but essential services threaten hospital financial viability and community care capacity. Current value-based payment design treats each service as an independent economic unit rather than recognizing cross-subsidization requirements, reflecting policymaker misunderstanding of hospital economics. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation’s recent initiatives have exacerbated this problem by focusing on individual service line performance metrics rather than institutional financial sustainability.

Academic Medical Center Challenges

Academic medical centers face particular pressure as healthcare transitions toward value-based payment models. Traditional profit centers (specialty procedures) face margin compression while historically unprofitable services (primary care, care coordination) become profit centers under capitated contracts. This transition requires fundamental restructuring of cross-subsidization relationships without losing essential community services during the adjustment period.

Successful navigation requires developing alternative revenue sources to replace procedure-based profits, restructuring cost bases to reflect new payment realities, and maintaining community benefit obligations despite financial pressures. Institutions must balance mission fulfillment with financial sustainability in an increasingly challenging economic environment.

Study Limitations

Medicare Cost Estimations This analysis employs several methodological constraints that warrant consideration. Cost estimation relies on institution-wide cost-to-charge ratios rather than detailed service-specific cost accounting, potentially understating cost variations between intensive and routine care services. The focus on Medicare payments excludes commercial insurance that typically reimburses at 150-200% of Medicare rates, significantly improving actual margins for most DRGs.

Academic Medical Center Complexity The analysis represents patterns typical of academic medical centers rather than institution-specific data, though the underlying cross-subsidization relationships reflect documented empirical findings. Academic medical centers demonstrate considerable variation in case mix, teaching intensity, and market position that influence both costs and payment rates. Additionally, healthcare costs and payment rates evolve continuously due to inflation and policy adjustments, making point-in-time analysis necessarily provisional.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Academic medical centers operate through cross-subsidization models where profitable elective procedures fund essential emergency care. This economic structure reflects healthcare’s unique market characteristics where demand for life-saving services proves price-inelastic and emergency care cannot be eliminated based solely on financial considerations.

Strategic Recommendations for Healthcare Leaders

Hospital executives should embrace portfolio management approaches when evaluating service line decisions, considering institutional mission and cross-subsidization requirements rather than individual service profitability. Strategic investments in high-margin services such as orthopedics and elective cardiac procedures can generate margin necessary to support community benefit obligations. Community benefit quantification should incorporate negative margin data to demonstrate concrete community value and support tax-exempt status justification.

Developing alternative payment streams, including philanthropic subsidies and academic-community partnerships, would lower cost burdens. Philanthropic partnerships offer supplemental support for specific service lines, particularly in pediatrics and oncology where mission alignment attracts donor interest. Academic-community partnerships can distribute costs across multiple institutions, enabling specialized services to achieve sustainable scale. Graduate medical education funding reforms could better recognize the true costs of teaching while supporting essential but unprofitable services that provide valuable clinical training environments.

Capital allocation decisions should reflect both direct service line returns and cross-subsidization contributions. Physician recruitment and retention strategies should acknowledge the revenue generation role of high-margin specialists while ensuring adequate support for essential but unprofitable services.

Policy Implications

Policymakers should evaluate Medicare DRG payment adequacy for critical care and emergency services to ensure sustainability of community safety nets. Healthcare market oversight should consider community impact when reviewing hospital transactions and consolidation activities that may disrupt cross-subsidization models.

Value-based payment model development should recognize interdependencies between profitable and mission-critical services rather than treating each service line as an independent economic unit. Alternative funding mechanisms for essential but unprofitable services deserve exploration to maintain community care capacity beyond traditional DRG payment reform. Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) payments provide partial subsidization for safety net functions – though funding remains inadequate relative to uncompensated care costs.

Future Directions

This analysis raises several questions warranting further investigation.

- First, how do cross-subsidization ratios vary between academic medical centers, community hospitals, and specialty facilities?

- Second, what happens to essential service provision when profitable service lines face sustained margin compression under value-based contracts?

- Third, can alternative organizational models (such as integrated delivery systems or public-private partnerships) maintain comprehensive care without relying on cross-subsidization?

Investigation of alternative funding mechanisms for essential but unprofitable services could inform policy development. Examining these questions would inform both institutional strategy and payment policy design.

Understanding cross-subsidization relationships proves essential for healthcare leaders navigating mission-margin tensions in an evolving payment landscape. Institutions that comprehend and strategically manage financial interdependencies will be better positioned to maintain comprehensive community care missions while achieving financial sustainability. The fundamental challenge lies in preserving the economic relationships that enable healthcare’s safety net function while adapting to new payment models and market pressures.